Just a few months ago, the United States experienced one of the most significant economic events of the past decade. No, it wasn’t a crash, a new currency, or an initial public offering. In fact, it was almost the opposite. Unlike most major market movers, this event did not come from Wall Street. It came from 38 million workers quitting their jobs. For seven record-setting months in a row, Americans have continued to voluntarily leave jobs in droves. This historic swing has been titled “The Great Resignation,” or more lightheartedly, the “Big Quit.”

“Voluntary quits,” as they are technically referred to, reflect a huge shift in power and precedent in the US labor market. For decades it has been the norm that there are almost always more qualified candidates than positions. Companies know this and have been happy to push workers harder and offer fewer benefits. However, household savings from stimulus programs lessened expenditures during the pandemic, and unemployment benefits which have often paid more than lost wages, have given workers more security to leave work that they dislike and wait for opportunities they see as more appealing. This combination of resigning from one job and being willing to wait until a better opportunity comes along has created a rare worker’s market, where employees are being offered better wages, benefits, and treatment. Waiting is easier not only because people have more money on hand, but also because when someone does eventually return to work, it will be for better compensation.

Responding to the Culture of Work

The financial boons and shifts of the pandemic seem to have triggered this sea change. But why now? Are workers always ready to abandon ship at the drop of a hat to sit and wait for better opportunities? More likely, this historic reaction is a response to an equally historic growth in worker discontent. From this perspective, the current wave of resignation has resulted from pressure that has been building for over 40 years.

American workers have consistently increased their productivity since 1950, yet pay has fallen behind, growing at less than a third of productivity’s pace. Not only have wages stagnated, but benefits and pensions have sharply declined. This trend toward more work for less benefit is not sustainable.

And this trend is in stark contrast to the expectations of work less than a century ago. In the 1950s, a low point of productivity in modern records, a single Ford plant worker’s annual income of $2,000 could pay for a car and a home in full in just five years. Jobs that we might today consider low level afforded families necessities and securities. Strong unions ensured steady wages and reasonable hours, leaving workers with time to be with their families and community.

Today much of this picture has changed. The outright prioritization of business has been on the rise while employee advocacy has declined. The median income of US workers aged 15 and over in 2020 was just $41,535, while the median home cost was over $400,000. A savings goal that may have taken five years to achieve sixty years ago may now take twenty. When we factor in economic volatility and the costs of education and childcare, and healthcare, building a life can feel impossible for many Americans. And these expenses are not luxuries. This puts families in the position of having to pay more each year for necessities with proportionally less. For many, the only way through has been to push harder, piecing together multiple jobs, saving fervently, and giving up the pleasures that can make life feel enjoyable. This, of course, has consequences. With less time and money, a considerable number of Americans don’t have the energy to engage with activities outside of work, especially with community.

Churches, local volunteer organizations, and even bowling leagues have seen a steady decline in membership over the last few decades. People are often too tired from work to extend themselves further. Sadly, this leads to a feeling of isolation that is often equally draining. Without friends, a sense of belonging, or a spiritual or religious practice, people are left searching for something that is central to the human experience – meaning.

Making Meaning At Work

At a loss for meaning elsewhere, work can eclipse other parts of life. More than ever before, work has become tied to our sense of identity and worth. PEW Surveys find that work now ranks higher in importance to many adults than relationships or children, with 95% of teens ranking work as more important than anything else.

Yet we know that for most of us, work alone cannot provide a sense of a fulfilled life. Altogether, modern working conditions create a pressure cooker – forcing people to work longer hours, making them feel their worth depends on it, and providing less compensation and stability. In short, the gap between the expectations and the reality of “good work” has opened for many into a wide chasm. These are the conditions that have led to burnout and quitting.

What is Burnout?

Burnout is defined by three key dimensions:

- Overwhelming exhaustion,

- Feelings of cynicism and detachment from a job, and

- A sense of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment.

The trends in work described above leave little surprise about why burnout is on the rise. Even before the pandemic, workers in education, healthcare, and Amazon warehouses were spending in excess of ten hours per day on their feet with hardly any rest. Not only are these employees worked hard, but they feel they are part of organizations that view them as largely disposable. These jobs give employees the feeling that they are always behind. Then, when performance indicators are met, they are likely to be given more work but not a share of the profits or benefits they generated.

More Than Tired

It is apparent that workers are not simply tired. For so many Americans, work has slowly but surely become an all-consuming inevitability, necessary to live but taking up most of life. Burnout is not just physical fatigue; it is a kind of weariness. It is a natural emotional response to an awareness that an endless cycle of living to work is deeply depleting. Hopes for work to be a source of meaning are frustrated when creating meaning for employees is not a priority for many employers. Even the most well-intentioned organizations will always need to put business ahead of the fulfillment of their workers.

A Chance for Change

For what may be the first time in half a century, workers have seized the chance to escape the crush and find space for their own lives. Is this just a fleeting trend? Or might we be in a pivotal moment in history that offers workers an opportunity for a new perspective and new direction?

How does work fit into your life?

If you are able, now is a great time to be asking difficult questions about the way work fits into your life. Are there sources of meaning in your life outside of work? Should there be more? Are you finding camaraderie at work? Although many of us do not have the luxury of making an immediate change or working less, everyone has the ability to investigate their work-life balance to see if it offers to sustain benefits including human connection.

Asking these kinds of questions can be difficult because the answers may point you toward the need for change. Whether it’s a change in your job or shifts in how you relate to coworkers, such changes will themselves require work, and for those already feeling burnt out, it may not seem worth it.

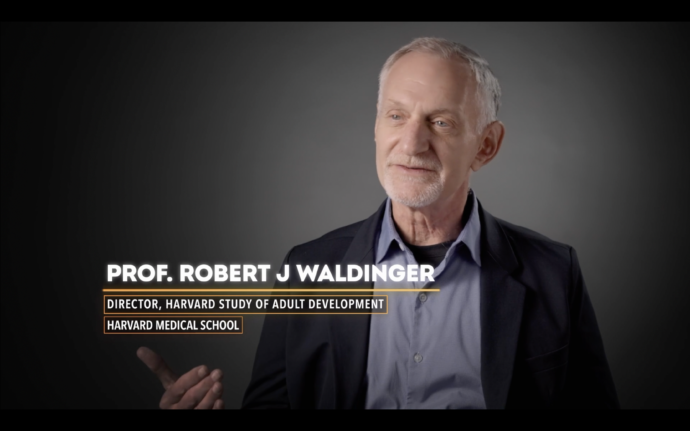

This is where many of us feel like we could use help. Thankfully there are resources for navigating transitions with support and wisdom. One of the best places to look is the Lifespan Research Foundation. At a time of great shared weariness, making a change can feel difficult, but Lifespan is here to support you make a step toward change. Small steps can carry you a long way, hopefully towards a life that feels more balanced and rewarding.